I'm nearing the end of my Shakespeare study. I started with the 37 plays, then read the poems and sonnets, before moving on to the apocryphal plays. The first of those I read was The Two Noble Kinsmen, which is sometimes included in Shakespeare's complete works. And in May I moved on to The History Of Cardenio. So yes, I’m getting deeper into the apocryphal plays now. Of course, The History Of Cardenio is one of the lost plays, but there are a couple of books that claim to be that play.

Double Falsehood is a play by Lewis Theobald that was published in 1728. He claimed it was based on William Shakespeare’s The History Of Cardenio, which he said he had more than one copy of. Though when he died, no copies were found among his possessions. The History Of Cardenio is considered one of Shakespeare’s lost plays, along with Love’s Labour’s Won (though I personally believe that the latter is simply another title for The Taming Of The Shrew). That play was based on a story within Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

Double Falsehood is a play by Lewis Theobald that was published in 1728. He claimed it was based on William Shakespeare’s The History Of Cardenio, which he said he had more than one copy of. Though when he died, no copies were found among his possessions. The History Of Cardenio is considered one of Shakespeare’s lost plays, along with Love’s Labour’s Won (though I personally believe that the latter is simply another title for The Taming Of The Shrew). That play was based on a story within Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

I read the Arden Shakespeare Third Series edition of The Double Falsehood Or The Distressed

Lovers by Lewis Theobald, edited by Brean Hammond and published in 2010.

This edition includes a nice long introduction, lots of notes, and several

appendices. The appendices include facsimiles of Thomas Shelton’s translation

of Don Quixote from 1612. In the

introduction, Hammond writes, “As both Eduard Castle and John Freehafer have

observed, the gaps, incoherences, inadequacies of motivation and awkwardnesses

of pace militate strongly against the view that Theobald composed it from

scratch, since he would have had to build in the imperfections (Castle, 196-7;

Freehafer). It is far more likely that there was an ur-text that he wanted to compress” (page 50). Then later in the

introduction: “Fleissner concedes that Double

Falsehood is based on a genuine Fletcher dramatization of the Cardenio

story. He discredits, however, Moseley’s ascription of Cardenio as a collaboration with Shakespeare, and claims that Theobald

himself must likewise have come to believe that Cardenio was solely written by Fletcher, making much of its

non-appearance in Theobald’s Shakespeare edition in 1733” (page 88). Hammond

then writes, “It seems to me that Theobald’s failure to regularize this

prosodic confusion – to tidy it up so that verse and prose are more clearly

distinguished, and to impart more regular iambic rhythms to passage where he

could easily have done so along Pope’s lines – is one additional strand of

evidence for the authenticity of his exemplars and against the hypothesis that

the entire project is a forgery” (page 138).

Related Books:

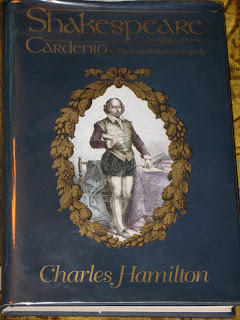

- Cardenio Or The Second Maiden’s Tragedy by Charles Hamilton - In

this volume, Charles Hamilton argues that The

Second Maiden’s Tragedy, which scholars generally believe to be by Thomas

Middleton, is actually the lost play Cardenio

by William Shakespeare. The book contains the entire play, and then a somewhat

detailed handwriting analysis, including examples of the handwriting of many of

the poets of Shakespeare’s day. Hamilton argues that the manuscript of The Second Maiden’s Tragedy is actually

in Shakespeare’s hand. It’s definitely an interesting argument. Hamilton, of

course, also addresses Theobald’s Double

Falsehood. Hamilton writes, “As Theobald stated that one of his three

copies of Cardenio had belonged to

the great actor, Thomas Betterton (c. 1635-1710), and was above sixty years old

(hence probably written in the early 1660s), it is very possible that Theobald

owned an original revision by Betterton, who might have transformed the tragedy

of Shakespeare and Fletcher into a ribald comedy for the delectation of the

merry monarch, Charles II. If so, all of Theobald’s copies may have been

slightly variant transcripts of Betterton’s version” (page 229). Published in

1994.

- The Trap Door: The Lost Script Of Cardenio by Andrew Delaplaine - This

is a novel aimed at teenagers, about a teenage actor who travels back in time

to 1594 and attempts to retrieve a copy of Shakespeare’s lost play, Cardenio. As you might have already

guessed, this book has some serious problems with the timeline. After all, Cardenio is known to be based on a story from Cervantes’ Don Quixote, and the first part of Don Quixote wasn’t published until 1605,

and the English translation by Shelton wasn’t published until 1612. So the idea

that Shakespeare wrote Cardenio in

1594 is just stupid. Delaplaine adds to the problem by writing, “The thinking

in his own time (by people like his father) was that Cardenio had been written between 1598 and 1602, not the Christmas

of 1594” (Page 114). Wrong. No one thinks it was written between 1598 and 1602.

That is this novel’s major error regarding the timeline, but certainly not its

only one. At one point, Charlie (the book’s protagonist) looks in the trunk

containing all of the company’s scripts, and inside he finds copies of Antony And Cleopatra, Macbeth and Hamlet. Again, the story takes place in 1594, a decade before

Shakespeare wrote Macbeth and

approximately thirteen years before he wrote Antony And Cleopatra. As for Hamlet,

there was an earlier play by that title that existed in 1594 (at noted in

Henslowe’s diary), but Shakespeare’s play wasn’t yet in existence. If the

author wanted Charlie to travel back to Elizabeth’s time (rather than that of

James), all he had to do is have Charlie search for Love’s Labour’s Won instead of Cardenio.

Delaplaine mentions that other lost script as being in the trunk. (I personally

think that Love’s Labour’s Won is

simply another title for Taming Of The

Shrew.) Anyway, that aside, it’s a somewhat interesting story. Charlie is a

teenager with a photographic memory, and is playing the role of Puck in a

production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream

at the Globe in London. He practices falling through the trap door, and when he

flubs a line he lands under the trap door at the old Globe in 1594. (Of course,

that’s another big problem, as the Globe wasn’t built until early 1599.) He

soon meets Shakespeare and Burbage and Marlowe, and even Queen Elizabeth. At

the Globe they are rehearsing Shakespeare’s new play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And soon it’s revealed that he’s at work

on another play, Cardenio. Charlie,

by the way, is a direct descendant of John Heminges. Charlie’s father is

described as “England’s greatest Shakespearean scholar” (page 7), and is

particularly obsessed with The History Of

Cardenio. So Charlie wants to somehow get a copy of the play back to the

present for his father. This book is not all that well written, and some lines

are just painful. Such as this one: “When you’re used to a pair of jeans and a

T-shirt, Charlie thought, all this finery took a little getting used to.” That

is a terrible line. By the way, according to this story, the first lines of Cardenio are: “Act One. Enter Cardenio

and Lucinda. Cardenio: Here in a sacred orchard we now find/Respite from sad

civil duties that bind/Us to our families, which we ‘scape” (page 120). Also,

it seems odd that the company is performing at the Globe in December. Published

in 2010.

No comments:

Post a Comment