Steve Martin mentions Shakespeare a couple of times in his collection of short comedic works, Pure Drivel, which was published in 1998. The first is in a piece titled "Writing Is Easy!" Steve Martin writes, "Once you have mastered these two concepts, vivid character writing combined with adjectives, you are on your way to becoming the next Shakespeare's brother" (p. 9).

And then, in "Times Roman Font Announces Shortage Of Periods," a piece on coping with a lack of periods, he writes: "Notice how these knotty epigrams from Shakespeare are easily unraveled:" (p. 32), and then includes two lines from Shakespeare. The first line is "Every cloud engenders not a storm," and after it is a happy face in place of a period. The line "For every cloud engenders not a storm" is from Act V Scene iii of The Third Part Of King Henry The Sixth, not one often quoted. The second line is "Horatio, I am dead," and it is followed by a sad face. That line, of course, is from the fifth act of Hamlet. However, that line in the play is followed by a semicolon, not a period, so it doesn't work with Steve Martin's intentions. Steve Martin should have included the slightly earlier line, "I am dead, Horatio," which does end with a period.

This blog started out as Michael Doherty's Personal Library, containing reviews of books that normally don't get reviewed: basically adult and cult books. It was all just a bit of fun, you understand. But when I embarked on a three-year Shakespeare study, Shakespeare basically took over, which is a good thing.

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Monday, July 28, 2014

Shakespeare Reference in Agatha Christie's The A.B.C. Murders

There is one Shakespeare reference in Agatha Christie's The A.B.C. Murders.

Near the end, when Hercule Poirot is on the verge of revealing his

conclusions regarding the case, he says, "Is it not your great

Shakespeare who has said, 'You cannot see the trees for the wood'?" (p.

174). The answer, by the way, is No. And in fact the next line of

Christie's book is "I did not correct Poirot's literary reminiscences"

(p. 174). The line is "cannot see the wood for the trees," and it was

written by Frederick Engels in the 1870s.

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Royal Deceit (1994) DVD Review

Royal Deceit (1994) stars Gabriel Byrne, Helen Mirren,

Christian Bale, Brian Cox, Steven Waddington, Kate Beckinsale and Tom Wilkinson. The

screenplay is by Gabriel Axel and Erik Kjersgaard. The film was directed by Gabriel Axel. Royal Deceit is actually not a Hamlet adaptation, but rather is based

on Shakespeare’s source material for the play. An opening credit states, “Based

on the Chronicle of Saxo Grammaticus.” Much of the story is the same, but it

pales greatly in comparison to Shakespeare’s work. This film shows just how

much Shakespeare brought to existing material. In short, it’s a terrible film,

in spite of an excellent cast.

The film suffers from a lot of poorly written and

unnecessary narration. It opens with narration about the tiny kingdom. “The peace of Jutland was shattered by the

murder of the king and his eldest son.” We learn that King Hardvendel was

supposedly attacked while on a hunting trip, and that only the king’s brother

survived. So much is told in voice over

at the beginning. For example: “It seemed

that upon hearing of his father’s death, Amled had gone mad. But Amled had

only assumed the disguise of madness. For his father’s ghost had come to him

demanding vengeance on his murderer, who still lived.” That’s right:

Instead of filming a ghost sequence, this film decides to just tell us about

it. In fact, we never see the ghost in this film.

Fenge (Gabriel Byrne), the king’s brother, tells Geruth

(Helen Mirren), the king’s wife, the story of the king’s death. “I blame myself,” he says. Indeed. She

dresses the wound which we just moments ago saw one of his men inflict upon him

at his command. And so we see how Fenge woos and seduces Geruth, which is

interesting. We also see the king’s funeral. At the funeral, Fenge says Amled

cannot be king until he regains his senses, and asks the crowd who they think

should be king. (Of course, it brings up an interesting point. If Amled had not

bothered to feign madness, then he would have automatically become king in this

story. So Fenge’s murder of the king and the king’s eldest son would have been

for naught. So, in fact, Amled’s mad plan only worked to help Fenge attain his

desired goals.)

The film then goes to a flashback to Fenge talking with

his men, saying: “What does my brother

have that I don’t have? He’s just older than I am.” The flashback continues

with Fenge leading the men to kill the king by hanging him.

When we return to the funeral, those very men call for

Fenge to be king. Fenge then announces that Geruth will be his wife. It must be

a very small kingdom, for only a handful of peasants have gathered for the

king’s funeral. It feels like a tiny village, hardly anything worth killing to

become king of.

After Amled (Christian Bale) shouts that someone has

stolen the king’s crown, Ribold (Steven Waddington), one of Fenge’s men, asks

Fenge if Amled is faking madness. Fenge isn’t sure, and isn’t sure how to find

out. Ribold suggests sending a woman to him. Obviously, Ribold is sort of the

Polonius figure, and the woman they send to Amled is a hint of the Ophelia

character. First we have to see Amled getting onto a horse backwards as part of

his mad act. (Really? Ugh.)

Well, Amled ends up having sex with the girl (why not?).

Afterwards he asks her straight out if Fenge had told her to make him love her.

And she nods her head yes. This is such a dull way to do this. In the play,

Hamlet comes to distrust Ophelia, but never asks her straight out if she’s

talking with him at the behest of Claudius. Anyway, this girl promises not to

tell Fenge anything, but Amled tells her to tell him he “barked like a dog and crowed like a rooster.” Would anyone fall for

Amled’s pathetic attempt at madness?

So then Ribold suggests leaving Amled alone with his

mother, and spying on the conversation. Voice over then tells us, “Fenge had no doubt that Amled knew him to be

Hardvendel’s murderer.” Geez, the film couldn’t show us that through Byrne’s

performance? The voice over also alerts us to Fenge’s decision to kill Amled.

Why show us anything at all at this point? Anyway, Ribold hides to hear the

conversation between Amled and Geruth, but in this version Geruth is unaware.

Somehow Amled immediately senses that Ribold is hiding in the room and stabs

him (but at no point thinks it is Fenge).

Each scene is so much poorer than the corresponding scene

in the play that I have to wonder why they wanted to film this in the first

place. Watching Helen Mirren in the closet scene made me wish they had just

decided to do Hamlet, for she (as

always) is wonderful, but could be doing so much more. In this version, Geruth

promises Hamlet that Fenge will not enter her bed again, something not in the

play. Everything is so easy in this version. Everything is black and white. The

characters are barely outlines of themselves.

We have the scene where Fenge asks Amled where Ribold is,

but unlike the play, in this version Geruth has not told Fenge that Amled has

killed Ribold. So why is he asking Amled this question at all? Like every other

scene, this is a poor substitute for the scene in Shakespeare’s work. Amled

says, “I suppose he’s with the pigs.”

(Earlier we saw him dump the body in with the pigs.)

Fenge decides to send Amled to England, as in the play.

He assigns two men to accompany Amled. But they have no prior relationship to

him, as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern do in the play, so why would Amled ever

trust them? And why would Fenge think he would? Amled then tells his plan to

Geruth, including that word of his death will come, to make sure that there is

no little bit of suspense in this film.

We see Amled on the boat, reading the message that Fenge

has sent to the Duke. But it’s a carving on wood, which makes it a bit silly,

especially as Amled begins to change the message. Pointless narration tells us,

“The message his uncle had sent to the

Duke of Lindsey was the proof that Amled had so long sought of his uncle’s

guilt.” Yeah, no shit. The voice over continues: “All Amled’s doubts and conflicts were laid to rest. There was to be

from this point on no impediment to his quest for justice and the avenging of

his father’s and brother’s murders.” (Compare that to Hamlet’s “O, from this time forth,/My thoughts be

bloody, or be nothing worth!”) And there are still thirty-eight minutes

left to the film.

For some reason, we have to watch the two men deliver the

message. The only good thing about this is that it provides us a scene with

Brian Cox, who plays the Duke. But the wood carving message is just too silly.

Amled catches the eye of the Duke’s daughter, Ethel (Kate Beckinsale). And we

have a pointless scene of Amled asking the Duke about his companions, and the

Duke explaining he had to hang them, as per the wishes of Amled’s uncle. There’s

an odd bit where Amled gets money from the Duke, demanding more than the Duke

offers. And then there’s a bit with Amled out riding a horse, and voice over

telling us what we can see him doing. And then there is perhaps the worst

battle scene ever to appear in a film (with what looks like small paper

cut-outs of soldiers in the background – seriously, look at the lower right

corner of the screen - it's hilarious) as a neighboring tribe attacks the Duke’s men.

The film spends quite a lot of time in England. And the

narration becomes more and more annoying, telling us the Duke is wounded just as we

see that the Duke is wounded. And then Amled gives one of those cliché rousing

speeches to the remaining men. There is a terrible fight scene between Amled

and the leader of that other tribe. That leader dies immediately from one small

knife wound. He doesn’t even have time to bleed. By the way, there is some

terrible looping in this scene, including someone shouting, “Take it easy!” Then we have another

pointless shot of the other tribe disarming. It just goes on and on. The film

is only eighty-five minutes, and it spends twenty-three of those in England,

away from the story.

Finally, with only fifteen minutes remaining, Amled

returns to Denmark with his new bride, Ethel. The scene where he returns and

faces Fenge is shockingly dull. And after Fenge and most of the others leave,

Fenge’s men stay behind with Amled, drinking. It makes no sense. And making

even less sense is that after these men have passed out, Amled doesn’t just

quickly dispatch them, but rather rolls each man up in a tapestry and then sets

fire to the place. What the fuck? And the tapestry bit was part of his plan all

along, for he told Geruth something about them before he left for England. Lighting

a fire is such a bad idea, for it puts innocent people at risk. The town’s

people have to rescue horses from the nearby stables and so on. Plus, the

building will then have to be rebuilt. Just stab the fuckers, Amled, you moron!

Oh well.

Anyway, Amled and Fenge have a very brief fight, which

Amled wins. So this version has a happy ending, with Amled alive and married

and now king, and his mom alive as well.

This film is worthwhile perhaps in as much as it shows us

just what a tremendous talent Shakespeare was. For when you remove Shakespeare

from a story, what you have left is hardly anything at all.

The DVD has no special features.

Monday, July 21, 2014

Shakespeare Study: The Tragedy Of Hamlet, Prince Of Denmark (revisited)

In my initial three-and-a-half-year Shakespeare study, I

read one play a month, and watched film adaptations and read books of critical

essays on each play. I hadn’t yet finished my three and a half years of

Shakespeare study when I decided that I would be revisiting key plays.

Basically, what I decided is that whenever I acquired more Shakespeare DVDs, I

would re-read the play or plays in question. I first returned to A Midsummer Night’s Dream,

then to The Taming Of The Shrew and The Tragedy Of Romeo And Juliet. And now I'm returning to The Tragedy Of Hamlet, Prince Of Denmark.

This time around I actually went back to the Signet

Classic Shakespeare edition, which is the first edition of Hamlet that I ever read (when I was fifteen or sixteen). And

actually, it is that particularly copy that I re-read this time. This edition

was edited by Edward Hubler, and originally published in 1963. The edition I

own is from 1987. It includes an introduction by Edward Hubler, as well as a

collection of criticism on the play. In the introduction, Hubler writes: “And

there will be no laughter at all when, at the close of Hamlet’s interview with

his mother, he drags the body of Polonius to the exit, remarking, ‘I’ll lug the

guts into the neighbor room.’ Then he pauses at the threshold to say, ‘Good

night, Mother.’ And he says it with all the tenderness he has, for she has

looked into her soul and repented, and in the contest with the King she is now

on Hamlet’s side. Mother and son are again at one. Bringing this about has been

the essential business of the scene, and the dragging of the body (though the

body must somehow be removed) is in no way necessary to it” (p. xxii). Later in

the introduction, Hubler writes: “He has seen the body of an old friend dug up

to make room for the body of the woman he loves. He has looked on death at what

is for him its worst. It is after the graveyard scene that the man who had

continually brooded on death is able to face it” (p. xxx).

In the section of criticism at the end of the book, A.C.

Bradley writes: “That Hamlet was not far from insanity is very probable. His

adoption of the pretense of madness may well have been due in part to fear of

the reality; to an instinct of self-preservation, a forefeeling that the pretense

would enable him to give some utterance to the load that pressed on his heart

and brain, and a fear that he would be unable altogether to repress such

utterance” (p. 210).

Robert Ornstein writes: “When he exposes his inner

feelings in the first soliloquy we realize that Claudius has completely missed

the point. Hamlet’s problem is not to accept his father’s death but to accept a

world in which death has lost its meaning and its message for the living – a

world in which only the visitation of a Ghost restores some sense of the

mystery and awe of the grave” (page 261-262).

Carolyn Heilbrun writes: “At the play, the Queen asks

Hamlet to sit near her. She is clearly trying to make him feel he has a place

in the court of Denmark” (p. 269).

Related Books:

- Hamlet Before During After by Ben Crystal - This

is a volume in The Arden Shakespeare’s Springboard Shakespeare series, and

offers a good introduction to the play.

Regarding Hamlet’s soliloquys, Crystal writes, “something takes place in

the middle act of the play that drives the Prince to talk to us more

frequently; and then the need to talk to us seems to evaporate in the final

act” (p. 10). Regarding Hamlet’s switch

from “thy” to “your” in “Go thy ways to a nunnery. Where’s your father?”

Crystal writes: “It’s a fascinating switch. In many productions, it’s the point

when Hamlet becomes aware that someone is watching him – either from the way

Ophelia behaves, a noise from where Polonius and Claudius are hiding, or simply

a realisation that he’s been left alone with Ophelia for the first time in a

long time, and that that’s unusual…” (p. 18). Regarding Hamlet’s writing,

Crystal writes, “And when he asks Horatio to tell his story so his name won’t

go down in history as a mad, murderous Prince, but an avenging, honourable son,

does he pass on his notebook to his friend?” (p. 29). About the Ghost, Crystal

writes: “Marcellus’ line Thou art a

Scholar, speak to it Horatio is fitting. Scholars knew Latin, and Ghosts

were supposed to be talked to in Latin (as Hamlet later does). Also, they

weren’t supposed to speak first; humans had to start the conversation” (p. 31).

Regarding Ophelia returning the letters to Hamlet, Crystal writes: “I like the

fact that Polonius only asked her to sit and read, and hopefully talk to him.

It’s Ophelia’s own idea to use the

opportunity – presumably the first in two months – to formally bring their

relationship to an end” (p. 63). And regarding Laertes and Ophelia, Crystal

writes: “A thought – towards the end of the scene, were it not for Claudius

keeping him behind, with his Laertes, I

must commune with your grief, perhaps he might have run after his sister,

and been there to save her from her fate…?” (p. 90). And regarding the setting

itself, Crystal writes, “The Royal Castle Kronberg, in the town of Helsingor,

north of Copenhagen in Denmark, is the basis for Shakespeare’s Castle Elsinore”

(p. 127). He continues: “A huge maze of a castle, Kronberg – the seat of

Denmark – is a dramatic place with long corridors, tapestries on every wall.

While the towering cliffs Horatio warns Hamlet of don’t feature in the real

Denmark, other features are incredibly accurate. Visiting Elsinore, there is a

set of stairs going up into the lobby, and the casements (the tunnels

underpinning the four long exterior walls) were originally used to house the

army, and later, as gaols. It gives Hamlet’s line Denmark’s a prison a different resonance. Three actors who later

become colleagues of Shakespeare performed at the Castle in 1585, and many

understandably guess that they told the budding young actor-writer about their

trip” (p. 128).

This book was published in 2013.

- Stay, Illusion! The Hamlet

Doctrine by Simon Critchley and

Jamieson Webster - This book, by a husband and wife team, has

some interesting thoughts and interpretations. Some of it I agree with, some I

don’t. Regarding the play within the play, they write: “What are the sufferings

of Hecuba or indeed Hamlet to us? Yet, Hamlet would seem to be suggesting that

the manifest fiction of theater is the only vehicle in which the truth might be

presented” (p. 8). Regarding the Ghost, they write: “The ghost is nothing, of course, so Barnardo

confesses that he has seen it, that is, not seen it” (p. 26). Maybe, maybe not.

But an interesting idea. They write: “Might not Horatio be Fortinbras’s spy?

Think about it: the play finishes with a cordial exchange between Horatio and

Fortinbras where the latter declares, ‘Bear Hamlet like a soldier to the stage.’

But in this interpretation, such magnanimity is not surprising because Hamlet

has served as the perfect, albeit unknowing, conduit by which Fortinbras could

accede to the throne of Denmark. The pretender Hamlet murders Claudius but has

the decency to kill himself in the process and with his ‘dying voice’ says ‘th’

election lights/On Fortinbras.’ Take it a step further: let’s imagine that

Horatio and his paid accomplices, Marcellus and Barnardo, agree to concoct the

story of the ghost in order to dupe an already intensely fragile,

grief-stricken, and almost-suicidal young aristocrat. Hamlet unwittingly adds

the patina of psychotic delusion to their deception, and this is more than enough

to motivate the young prince to kill his uncle and clear the path for

Fortinbras. Horatio knows everything from the get-go because Hamlet is his

puppet and the ghost is his ruse” (p. 49). On the next page they admit that this

idea is far-fetched. No shit. It’s an interesting thought, but Bernardo is

clearly nervous and frightened by the Ghost before Hamlet ever appears. There

is a lot of stuff in this book about Freud and psychoanalysis that is loosely

related to Hamlet. And the writers

don’t understand what the word literally

means. They write, “The person identifies with the lost object and is literally

crushed by it” (p. 123). Wrong. And then again: “The lost other is literally

composed of desire” (p. 136). I don’t think anything can be literally composed

of desire. They draw a parallel

between Hamlet and Laertes: “So if Laertes is Hamlet’s double, then it is no

surprise that the play ends with their double murder. We have two groups, one a

reduplication of the other: Polonius, Laertes, Ophelia; and Claudius, Hamlet,

and Gertrude. By the end of the play Laertes is uncannily in the same position

as Hamlet: he has a father murdered, Ophelia lost, the support of the rabble

for the throne; he acts as an organ for Claudius’s scheming, and he desperately

seeks revenge” (p. 139). About Ophelia, the authors write: “She is always taken

as something to be used, as bait. No

one ever asks her what it is that she

wants. In her madness we see her desire explode onto the stage, immersed in a

voracious sexuality invariably denied to her” (p. 147). As for the book’s

title, it comes from a passage quoted from Nietzsche: “Knowledge kills action;

action requires the veils of illusion – that is the Hamlet Doctrine” (p. 195).

The authors write, “Hamlet’s inaction is caused not by a lack of energy but by

the knowledge that action is futile” (p. 202). And in their conclusion, the

authors state, “For us, at its deepest, this is a play about shame, the nothing

that is the experience of shame” (p. 228).

This book was published in

2013.

- Murder Most Foul: Hamlet Through

The Ages by David Bevington - In

the preface, author David Bevington explains: “The central argument of this

book is that the staging, criticism, and editing of Hamlet go hand in hand over the centuries, from 1599-1600 to the

present day, to such a remarkable extent that the history of Hamlet can be seen as a kind of paradigm

for the cultural history of the English-speaking world” (p.vii). Regarding the

earlier Hamlet, Bevington writes: “The likeliest candidate for authorship of a

lost Hamlet play in the years around

1589 would appear to be Thomas Kyd. His profile fits Nashe’s satirical

description of one who has left the trade of ‘noverint’ or copier of writs to

become a hack writer turning out whole Hamlets,

that is to say, handfuls, of overwrought tragical speeches” (p. 17). Regarding

the end of the Ghost scene, Bevington writes, “Hamlet makes a point of exiting

with the soldiers and Horatio together, rather than allowing them to yield him

precedence, as a way of insisting on their brotherhood of secrecy” (p. 35). Regarding

the Ghost’s line “Unhousled, disappointed, unaneled,” Bevington writes: “The

terms here, ‘Unhousled, disappointed, unaneled,’ have precise technical meanings

in Catholic theology. To die ‘unhousled’ is to die not having received the

Eucharist in the sacrament of Last Rites or Extreme Unction. This sacrament

requires an anointing by the priest of a person in danger of death, accompanied

by a set form of words, aimed at ensuring the eternal health of the soul. To be

‘disappointed’ is to be inadequately furnished for one’s journey into death. ‘Unaneled’

again means to have died without receiving Extreme Unction. Shakespeare does

indeed show here his familiarity with Catholic practice” (p. 63). Regarding Hamlet’s

supposed madness, Bevington writes, “Whether he is ever truly mad is a question

much discussed, as we shall see, though the text gives little if any support

for the notion that he really is so” (p. 68). Regarding the killing Polonius,

Bevington writes: “Hamlet appears to derive two insights form this miscarriage

of his plans. One is that swift, resolute action is not the uncomplicated

solution one might have hoped. The other is that he, Hamlet, will have to pay

for this killing of Polonius, just as Polonius has paid the price of his

meddling” (p. 70). Regarding the Restoration, Bevington writes: “Restoration

spectators and readers of Shakespeare generally applauded ‘improvements’ to his

text designed to elevate him to the high poetic status he deserved. Actors and

editors alike excised secondary characters, unified action according to the

classical unities, and attempted to render Hamlet

and other plays more symmetrical and spectacular by the incorporation of scenic

effects” (p. 92). He then writes, “The early eighteenth century is also the era

in which scholarly editing of Shakespeare’s texts began” (p. 93). He also

writes, “Hamlet criticism and editing

in the eighteenth century, then, is generally neoclassical in tone and method,

preferring classical regularity and decorum, albeit with some large exceptions

made for Shakespeare’s genius. Criticism of this period manifests an abiding

interesting in character more than in plot or theme. It seeks to appraise and

understand the moral purpose of the protagonist, and to measure the validity of

the play’s denouement by the standards of poetic justice. At the same time, the

late years of the century exhibit signs of change” (p. 106). About Henry

Irving, Bevington writes: “Irving’s interpretation of Hamlet was of a man

stricken with love for Ophelia – a not surprising emphasis, given the sympathy

expressed by many nineteenth-century critics for the suffering of such a

tender, innocent, and beautiful young woman. Even as Hamlet mocked her in their

painful overheard conversation (3.1), Irving’s Hamlet could not hide the depths

of his feeling for her; in the words of a contemporary reviewer, ‘his whole frame

seemed to tremble with heartfelt longing.’ To put this failed love relationship

in a fuller perspective, and to bestow on Hamlet the emotional sensitivity

worthy of such a lovelorn young man, Irving followed some of his predecessors

in deleting Hamlet’s soliloquy of implacable determination to send the kneeling

Claudius’s soul to hell” (p. 125). Regarding Bernardo, Bevington writes, “This

anxiety can explain why Bernardo asks the opening question, ‘Who’s there?’ when

it is Francisco, the guard currently on watch, who should issue that challenge”

(p. 130). Regarding Mark Rylance as Hamlet, Bevington writes: “In the Globe

space that invites chumminess and overstatement, Rylance was resourceful in

developing a rapport with audiences. He pointedly hurled at them Hamlet’s line

about how ‘groundlings’ are ‘capable of nothing but inexplicable dumb shows,’ then

adding, after they had objected vociferously at this, ‘and noise’” (p. 180). Bevington writes: “The phrase ‘Hamlet without

the Prince’ has entered the language as signifying a performance or an event

lacking the principal actor or central figure. The origin of this phrase is an

account in the London Morning Post,

September 1775, telling of a touring company which suddenly discovered that its

leading player had run off with the innkeeper’s daughter. The company had to

announce to the audience that ‘the part of Hamlet is to be left out, for that

night’” (pages 198-199).

This book was published in

2011.

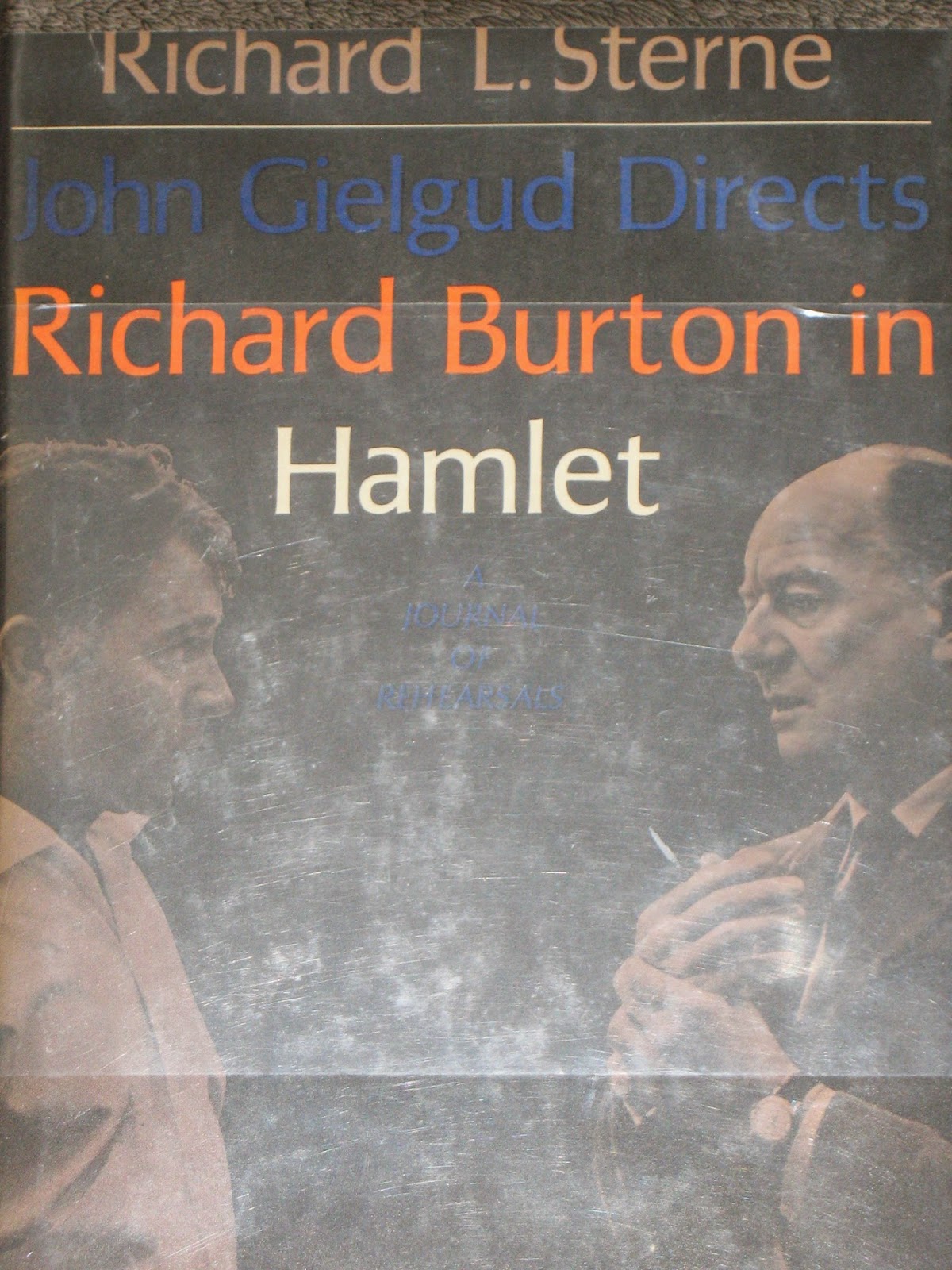

- John Gielgud Directs Richard

Burton In Hamlet by Richard L.

Sterne - This is a really interesting book, detailing

the rehearsal process of a production of Hamlet.

Richard L. Sterne secretly recorded the rehearsals, and so much of the book is

actual transcripts. Early on in the rehearsals, Gielgud says: “All the people

in the play are shut up in this castle. You play that, really, all through the

play. There is this curious feeling, except on the battlements and in the churchyard,

that they are all really locked in the castle, in a miasma of corruption and

sensuality. It isn’t until Fortinbras comes at the end that the whole thing

opens and all are free” (p. 17). Regarding Rosencrantz and Guildenstern,

Gielgud says: “When Hamlet says ‘What a piece of work is a man,’ they are the men he is referring to, and

he plays it to them as an expression of what he wants them to represent.

Otherwise, they just stand there with nothing to do and look like supers” (p.

29). Regarding the scene where Claudius is trying to pray, Gielgud says to

Richard Burton: “Hamlet is hurrying to his mother and stumbles on the King, and

in a frenzy grabs the sword and almost kills him without reflecting. The lines

and business must all go rapidly. I think you should whisper the speech” (p.

53). Regarding Hamlet’s departure and return, Gielgud says: “The fight with the

pirates and Hamlet’s departure are in the play to show the feeling of a

journey. Shakespeare does the same in Winter’s

Tale and Tempest. He was

fascinated by journeys because they were so much more important then and took

so much longer. And it has a tremendous effect on Hamlet in this play because

he comes back fantastically ready to carry out his mission without

complications. It’s only the sight of Ophelia’s body and Laertes jumping into

the grave, in which Hamlet suddenly sees this young man whom he always had

liked behaving exactly as he had done

when his father died, in a sort of

hysteria of grief. That makes him jump in and do all that violent stuff” (p.

56). The book contains the entire play as performed in this production, with

lots of notes on stage directions. They had an interesting take on the “Words,

words, words” line: “Words. (POLONIUS starts

to speak, but HAMLET cuts him off by

repeating more sharply) Words! (POLONIUS again tries to explain, pointing at the book and taking a step toward

him) WORDS!” (p. 186). The book ends with the transcripts of interviews

done with Richard Burton and John Gielgud. Regarding the duel with Laertes,

Gielgud says “That’s just a game, like football is to us. But he knows the end

is at hand. The King very cunningly sent Osric to play the fool in order to

divert Hamlet’s suspicion so that the wager will seem trivial and so he won’t

take it too seriously” (p. 297).

This book was published in 1967.

- William Shakespeare’s Hamlet adapted by Rebecca Dunn; illustrated by Ben

Dunn - This is a volume in the Graphic Shakespeare

series by Graphic Planet. It’s only forty-eight pages, and so is little more

than an outline of the play, just a few lines from most scenes. When the Ghost

tells of his murder, there are illustrations of Claudius flirting with Gertrude

and pouring the poison in the King’s ear. The Ghost doesn’t urge the others to

swear, and so the “Rest, rest, perturbed spirit” line is cut. Shockingly, a bit

of the Reynaldo scene is included. Because so much is cut, there are short

descriptions to fill in some of the information otherwise lost. However, we

also get this: “At the castle, the queen hires two of Hamlet’s friends to spy

on him” (p. 15). That’s making a bit of a jump from the information given in

the play. Many of the most famous lines are cut, including Polonius’ “brevity

is the soul of wit.” Oddly his “Though this be madness, yet there is method in ‘t”

is left in, but not Hamlet’s lines that lead him to say it. So it comes out of

nowhere. I think this book might be quite confusing to any people who are not

already familiar with the play. The “What a piece of work is a man” speech is

cut. It goes from “all custom of exercises” straight to “Man delights not me,”

an awful cut. Only the beginning of “To be or not to be” is included. It ends

with “mortal coil,” which is odd because that is mid-sentence, mid-thought. The

authors of this book clearly do not understand the play. No noise from behind

the arras alerts Hamlet to the presence of Claudius and Polonius, so Hamlet

exits, seemingly unaware of being watched. All the stuff about the recorder is

cut. The scene where Rosencrantz and Guildenstern ask Hamlet the location of Polonius

is cut. The “How all occasions do inform against me” speech is cut. Ophelia’s

mad scene is completely cut, which is ridiculous, especially as Laertes still

says “a sister driven into desperate terms” (p. 34). Act IV Scene ii is cut.

Another insane choice is that everything regarding Yorick is cut. The

gravedigger holds up a skull, but the next panel shows the funeral procession.

Hamlet puts his hood up and sneaks over to the coffin and sees Ophelia, rather

than learning of her identity through Laertes’ lines. All of the dialogue

between Hamlet and Horatio is cut (so no “special providence in the fall of a

sparrow”), as is Osric. Instead we get a very misleading panel: “Laertes and

Hamlet take their fight back to the castle…” (p. 40). Wrong, wrong, wrong. That

is so far removed from what Shakespeare wrote that all copies of this book

should be force-fed to its authors. Hamlet says “Is thy union here,” though all

of Claudius’ lines about the union are cut. More crazy cuts are at the end.

Gone is “The rest is silence.” Gone is Horatio’s famous speech. But Fortinbras

is left in. This is an absolutely terrible book and should be avoided.

It was published in 2009.

- Wittenberg: A

Tragical-Comical-Historical In Two Acts

by David Davalos - This play takes place before the events of Hamlet, with Hamlet at school, his major

as yet undeclared. The focus, however, is the dialogue between John Faustus and

Martin Luther. Faustus teaches philosophy, and Luther teaches theology at the

school. There are anachronistic jokes, such as “Two-stein minimum” (p. 9), and references to The Who’s “The Seeker,”

Robert Palmer’s “Bad Case Of Loving You (Doctor, Doctor)” and “Que Sera Sera.”

There are plenty of references to Hamlet.

For example, Faustus says: “…despite this being a Catholic university, we are

not going to be restricting ourselves to studying the philosophies of the

Church. There are, after all, more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt

of in its theology” (p. 12). At one point Hamlet says, “Being and not-being,”

to which Faustus responds, “Those are the questions, yes” (p. 18). And in that

scene, there is some business with a skull. There are more references to that

famous speech. Faustus says, “To believe or not to believe,” and Hamlet

responds, “That is the question” (p. 19). Still later, Faustus says, “To be or

not to be,” and Hamlet asks, “That is the question?” (p. 46). Faustus also

says, “You must shuffle off this moral coil” (a play on “mortal coil”). There

are plenty of other references to the play, including a reference to The Murder Of Gonzago, with Faustus

saying, “I hear they’re making it into a play” (p. 24). Hamlet and Laertes play

tennis, and of course there are several references to their duel in Hamlet. For example, Laertes says, “These

racquets have all a length?” (p. 37). The Judge says, “An out! A very palpable

out” (p. 37). The ghost of Mary appears to Hamlet much the way the ghost of his

own father appears to him in Hamlet.

She even bids him, “Remember me!” And the word association game has many

references to Hamlet. Faustus also

says, “After all, there really is no ‘good’ nor ‘bad,’ but thinking makes it so”

(p. 50), and Luther says, “His Providence is found even in the fall of a

sparrow” (p. 50), so clearly both of them have an impact on Hamlet’s thinking. There

is also a reference to The Tempest,

with Hamlet saying, “No more than such like stuff as dreams are made upon” (p.

10). In the play, Faustus nails Luther’s points to the church door. At the end,

Hamlet learns of his father’s death. There is also a joke on Shakespeare’s

play, with Faustus saying to Hamlet, “Live your life so that I may never have

to read of the tragedy of King Hamlet, yes?” (p. 61).

This book was published in

2010.

(Note: I've been posting reviews of film versions of Hamlet as separate blog entries.)

- Ghost Light by Tony Taccone - This

play is based on the experiences of Jon Moscone, whose father, Mayor George

Mascone, was assassinated along with Harvey Milk by Dan White in 1978. Hamlet is a significant part of the

story. In an early scene, Jon gets a message on his machine about costumes for

a production of Hamlet. He teaches a

master class in acting, and talks to his students about the Ghost in Hamlet. About Gertrude in the final

Ghost scene, he tells his students: “She’s watching her only son lose his mind

right in front of her very eyes. Her heart is breaking. And here’s the real

deal: she is actively trying to stop that from happening. She tries to control

him, to keep him from losing it, to keep her pain at bay” (p. 17). Jon’s advice

to the guy playing Hamlet, regarding the character’s seeming inability to act,

is: “You know somewhere, somewhere you know that in order to kill your father’s

murderer you have to kill off a part of yourself. The best part of your deepest

self. You have to learn how to hate. Become a villain to kill a villain. You

have to learn to hate yourself” (p. 28). References to the play are made by

other characters. For example, Prison Guard says, “Come on, let’s lug the guts

out of this here limbic system” (p. 20), a reference to Hamlet’s line about

Polonius. Louise says to Jon: “You were making a case for the time of the play

being a time of darkness and despair, and that if the court was really that

corrupt then Hamlet’s father had to be implicated as well, that he might have

been something less than the hero his son wants him to be. Which explains why

Hamlet is so completely paralyzed” (p. 48). Toward the end of the play, there

is a series of auditions for the part of the Ghost, and then Jon reads part of

the Ghost’s speech: “I am thy father’s spirit/Doomed for a certain term to walk

the night…” (p. 93).

This book was published in

2011.